You are viewing the article 7 Facts About Indira Gandhi at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

Indira Nehru Gandhi was a complex woman whose leadership in India continues to have repercussions to this day. It was on January 24, 1966, that she was sworn in as that country’s first female prime minister; in honor of that anniversary, here are seven fascinating facts about her incredible life.

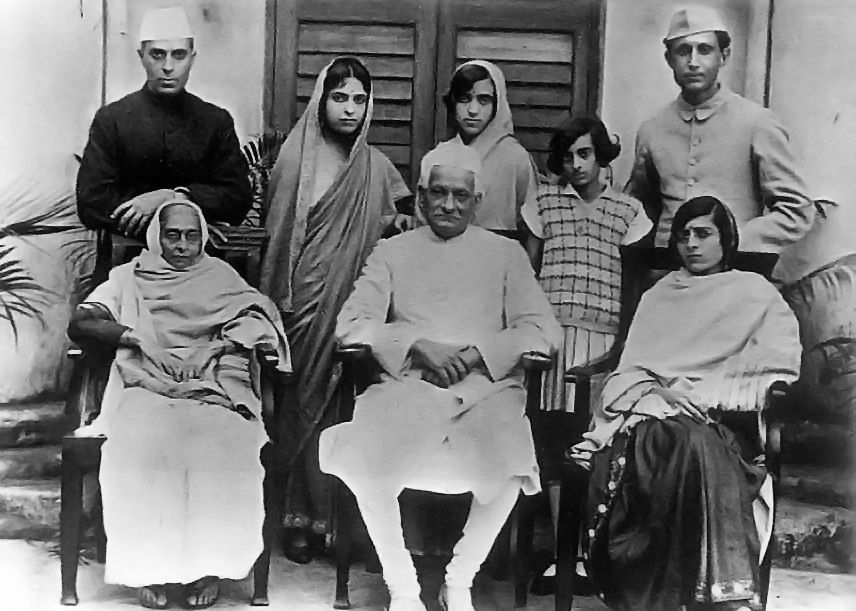

Her life involved politics from a young age

Almost from the moment she was born in 1917, Indira Nehru’s life was steeped in politics. Her father, Jawaharlal Nehru, was a leader in the fight for India’s independence from British rule, so it was natural for Indira to become a supporter of this struggle.

One tactic of India’s nationalist movement was to reject foreign — particularly British — products. At a young age, Indira witnessed a bonfire of foreign goods. Later, the 5-year-old chose to burn her own beloved doll because the toy had been made in England.

When she was 12, Indira played an even bigger role in India’s struggle for self-determination by leading children in the Vanar Sena (the name means Monkey Brigade; it was inspired by the monkey army that aided Lord Rama in the epic Ramayana). The group grew to include 60,000 young revolutionaries who addressed envelopes, made flags, conveyed messages and put up notices about demonstrations. It was a risky undertaking, but Indira was happy to be participating in the independence movement.

Her marriage wasn’t widely supported

Indira’s father was a close associate of Mahatma Gandhi. However, the fact that Indira ended up with the same last name as the iconic Indian leader wasn’t due to a connection with the Mahatma; instead, Indira became Indira Gandhi following her marriage to Feroze Gandhi (who wasn’t related to the Mahatma). And despite the fact that Indira and Feroze were in love, theirs was a wedding that few people in India supported.

Feroze, a fellow participant in the struggle for independence, was Parsi, while Indira was Hindu, and at the time mixed marriages were unusual. It was also out-of-the-norm not to have an arranged marriage. In fact, there was such a public outcry against the match that Mahatma Gandhi had to offer a public statement of support, which included the request: “I invite the writers of abusive letters to shed your wrath and bless the forthcoming marriage.”

Indira and Feroze wed in 1942. Unfortunately, though the pair had two sons together, the marriage was not a great success. Feroze had extramarital liaisons, while much of Indira’s time was spent with her father after he became India’s prime minister in 1947. The marriage ended with Feroze’s death in 1960.

A refugee crisis put pressure on her

In 1971, Indira faced a crisis when troops from West Pakistan went into Bengali East Pakistan to crush its independence movement. She spoke out against the horrific violence on March 31, but harsh treatment continued and millions of refugees began to stream into neighboring India.

Taking care of these refugees stretched India’s resources; tensions also mounted because India offered support to independence fighters. Making the situation even more complicated were geopolitical considerations — President Richard Nixon wanted the United States to stand by Pakistan and China was arming Pakistan, while India had signed a “treaty of peace, friendship and cooperation” with the Soviet Union. The situation didn’t improve when Indira visited the United States in November — Oval Office recordings from the time reveal that Nixon told Henry Kissinger the prime minister was an “old witch.”

War began when Pakistan’s air force bombed Indian bases on December 3; Indira recognized the independence of Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan) on December 6. On December 9, Nixon directed a U.S. fleet to head for Indian waters — but then Pakistan surrendered on December 16.

The war’s conclusion was a triumph for India and Indira (and, of course, for Bangladesh). After the conflict had ended, Indira declared in an interview, “I am not a person to be pressured — by anybody or any nation.”

Millions were sterilized when she declared a state of emergency

In June 1975, Indira was found guilty of electoral malpractice. When rivals began advocating for her removal as prime minister, she opted to declare a state of emergency. Emergency rule would be a dark moment for India’s democracy, with opponents imprisoned and press freedoms limited. Perhaps most shockingly, millions of people were sterilized — some against their will — during this period.

At the time, population control was seen as necessary in order for India to prosper (Indira’s favored son and confidant, Sanjay, became particularly focused on reducing the birth rate). During the Emergency, the government directed its energies toward sterilization, with a focus on the simpler procedure of vasectomies. To encourage men to undergo the operation, incentives such as cooking oil and cash were offered.

Then government workers began to be required to meet sterilization quotas to get paid. Reports came out that vasectomies had been performed on boys, and that men were being arrested, then sent to be sterilized. Some began sleeping in fields so as to avoid sterilization teams. According to a 1977 article in TIME magazine, between April 1976 and January 1977, 7.8 million were sterilized (the initial target had been 4.3 million).

At the beginning of 1977, Indira called for elections, ending her Emergency rule. She’d expected to win this vote, but the fear and worries brought on by the sterilization policy contributed to her defeat at the polls, and she was kicked out of office.

She clashed with her daughter-in-law

In 1982, a disagreement between Indira and daughter-in-law Maneka led to a showdown. Practically from the moment Maneka wed Sanjay and entered Indira’s household, the younger woman didn’t fit in. After Sanjay died in 1980 (he was killed in a plane crash), tensions rose further. Things came to a head when Maneka defied Indira to attend a rally of Sanjay’s former political allies (which didn’t help the political interests of Rajiv, Sanjay’s brother).

As punishment, Indira ordered Maneka to leave her house. In return, Maneka made sure the press captured her bags being unceremoniously left outside. Maneka also publicly decried her treatment, stating, “I have not done anything to merit being thrown out. I don’t understand why I am being attacked and held personally responsible. I am more loyal to my mother-in-law than even to my mother.”

Though the prime minister got Maneka to move out, she paid a price as well: Maneka took her son, Varun, with her, and being separated from a beloved grandson was a blow for Indira.

She was close with Margaret Thatcher

As a female leader in the 20th century, Indira Gandhi was a member of a very small club. Yet she had one friend who could understand what her life was like: the Iron Lady herself, Britain’s Margaret Thatcher.

Indira and Thatcher first met in 1976. They got on well, despite the fact that Indira was engaged in her undemocratic Emergency rule at the time. And when Indira was temporarily out of power after her electoral defeat in 1977, Thatcher didn’t abandon her. The two continued to have a good rapport after Indira returned to power in 1980.

When Thatcher came close to being killed by an IRA bomb in October 1984, Indira was sympathetic. Following Indira’s own assassination a few weeks later, Thatcher ignored death threats to attend the funeral. The note of condolence that she sent to Rajiv stated: “I cannot describe to you my feelings at the news of the loss of your mother, except to say that it was like losing a member of my own family. Our many talks together had a closeness and mutual understanding which will always remain with me. She was not just a great statesman but a warm and caring person.”

Her son succeeded her after her death

One significant factor that buoyed Indira’s political career was her heritage. As the daughter of India’s first prime minister, the Congress Party was happy to put her in a position of leadership, then later selected her to become prime minister.

After Indira’s 1984 assassination, her son Rajiv succeeded her as prime minister. In 1991, he was also assassinated, but the Nehru-Gandhi clan still wasn’t done with politics: though Rajiv’s widow, Sonia, initially declined the Congress Party’s request to step into a leadership role, she eventually became its president. By the 2014 election, Rajiv and Sonia’s son Rahul had joined the Congress Party as well; however, the party went on to experience a big loss at the polls. At a press conference, Rahul admitted, “The Congress has done pretty badly, there is a lot for us to think about. As vice president of the party I hold myself responsible.”

Yet not all Gandhis fared poorly in the 2014 election — as members of the victorious Bharatiya Janata Party, Maneka Gandhi and her son Varun are now in power, with Maneka serving as minister of women and child development (though considering her acrimonious relationship with Maneka, this development likely wouldn’t thrill Indira). And despite their poor showing in 2014, the Congress Party refused to accept Sonia and Rahul’s resignations. It seems that various members of Indira’s family will continue to play a role in Indian politics for the foreseeable future.

Thank you for reading this post 7 Facts About Indira Gandhi at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: