You are viewing the article 12 Presidential Nicknames and Their Unusual Origins at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

The nicknames given to America’s commanders in chief have been as varied as the people themselves. Some have showcased military victories and qualities of leadership to propel candidates onto the national stage, while others have revealed the darker side of American politics itself. Here’s the story behind some legendary presidential nicknames:

James ‘Little Jemmy’ Madison played a critical role in the birth of America

Virginia-born James Madison co-authored the Federalist Papers with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, earning the nickname “Father of the Constitution” for his role in drafting and championing the landmark document.

But this political powerhouse Founding Father was also the shortest president in American history, likely standing just 5 feet 4 inches tall. Known to his family and friends as Jemmy, his small stature and weak physical appearance led some detractors to disparage him as “Little Jemmy” or “His Little Majesty.” One contemporary quipped that he was “no bigger than half a piece of soap.” Author Washington Irving was no kinder, noting at Madison’s 1809 inauguration that he resembled a “withered little apple.” By comparison, his fellow Virginian Thomas Jefferson, who at 6 feet 2 inches towered over most of his countrymen, was dubbed “Long Tom.”

Andrew ‘Old Hickory’ Jackson rode a populist wave to the White House

The first westerner to become president, Andrew Jackson was orphaned at a young age and had little formal schooling but became a lawyer and politician in his adopted Tennessee. When war broke out with Great Britain in 1812, the ever-ambitious Jackson saw an opportunity. He lobbied hard for a military appointment, and despite his reputation for brashness and his fierce temper, he was named major general of the Tennessee militia.

During campaigns against the Creek Indians (British allies during the war), Jackson’s steadfastness and resolve earned him the admiration of his troops, who claimed he was as strong as a hickory tree. His victories, including the climactic Battle of New Orleans in 1815 made him a national hero, and his supporters capitalized on his fame, pushing him as a candidate for president. Jackson lost a closely contested race in 1824, but “Old Hickory” prevailed in 1828, serving two controversial terms.

Zachary ‘Old Rough and Ready’ Taylor’s military victories help make him president

Zachary Taylor was born in Virginia and grew up on the Kentucky frontier, the child of prosperous farmers. Like Jackson, he had little formal education, and in 1808 he joined the U.S. Army as a first lieutenant. He would spend the next 40 years in the military, leading troops in the War of 1812, Black Hawk War and Second Seminole War.

Taylor was a down-to-earth, unpretentious leader who readily shared the difficulties and privations of his fellow soldiers. His willingness to get into the muck with his men earned him their undying loyalty — and the nickname “Old Rough and Ready.” He became a national star thanks to his victories during the Mexican-American War at Palo Alto, Monterrey and Buena Vista, earning him comparisons to George Washington and Jackson. His homespun manner made him an appealing political candidate. Just months after the war formally ended in 1848, he was elected president, but he served just 16 months before dying of gastroenteritis

John ‘His Accidency’ Tyler’s enemies considered him an unexpected president

John Tyler was born into the Virginia aristocracy, the son of a judge and politician who had been a college roommate of Jefferson. A lifelong believer in states’ rights who fought against growing federal powers, Tyler shocked his supporters and allies when he broke with fellow Democrat Jackson and his party, resigning his Senate seat in protest in 1836. His maverick reputation (and background as an enslaved-holding Southerner) made him an appealing candidate to balance the presidential ticket for the Whig Party in 1840. Because no president had ever died in office, few worried that Tyler would succeed the head of the ticket, William Henry Harrison. Harrison was an old war hero, thanks to his 1811 victory over Native American leader Tecumseh at the Battle of Tippecanoe, and the campaign slogan and song of “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” helped propel the pair into the White House.

But just a month after being sworn in, Harrison was dead, after contracting a cold-turned-pneumonia while delivering a long inaugural speech in a cold rain. Although the Constitution did not explicitly state that the vice president automatically assumed the full powers of the presidency, Tyler did just that. But he soon came into conflict with fellow Whigs, and his growing list of political enemies quickly dubbed him “His Accidency.” A man without a party, he briefly ran for election in 1844 before withdrawing his candidacy for lack of support.

Abraham ‘Honest Abe’ Lincoln had a number of nicknames

America’s 16th president came from famously humble origins, born in a one-room log cabin in Kentucky. He had little formal schooling but was self-educated and ambitious. He worked a series of odd jobs and used his lanky frame to his advantage as a wrestler to chalk up a reported 299-1 record, earning him one of his first nicknames, “Grand Wrestler,” and a spot in the National Wrestling Hall of Fame.

By his mid-20s, Abraham Lincoln had moved to New Salem, Illinois, where he worked as a shopkeeper, postmaster and store owner. It was here that Lincoln earned his reputation for honesty, reportedly chasing customers out of his store if he had accidentally shortchanged him. “Honest Abe” became a lawyer and settled in Springfield where he was elected to one term in Congress. When Lincoln unsuccessfully ran against Stephen Douglas in an 1858 Senate race, Douglas confided in a friend that Lincoln’s reputation for truthfulness and honesty made him an attractive candidate.

When Lincoln ran for president in two years, friends and supporters looked to turn his humble background to his advantage, marching into the Republican National Convention in Chicago with a set of fence rails that they claimed Lincoln, the “Railsplitter,” had split in his youth. The nickname quickly caught on, helping propel Lincoln into the national consciousness. As president, Lincoln’s leadership and evolution on the issue of slavery led to his issuing the Emancipation Proclamation and championing passage of the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery, earning him one final nickname, “Great Emancipator.”

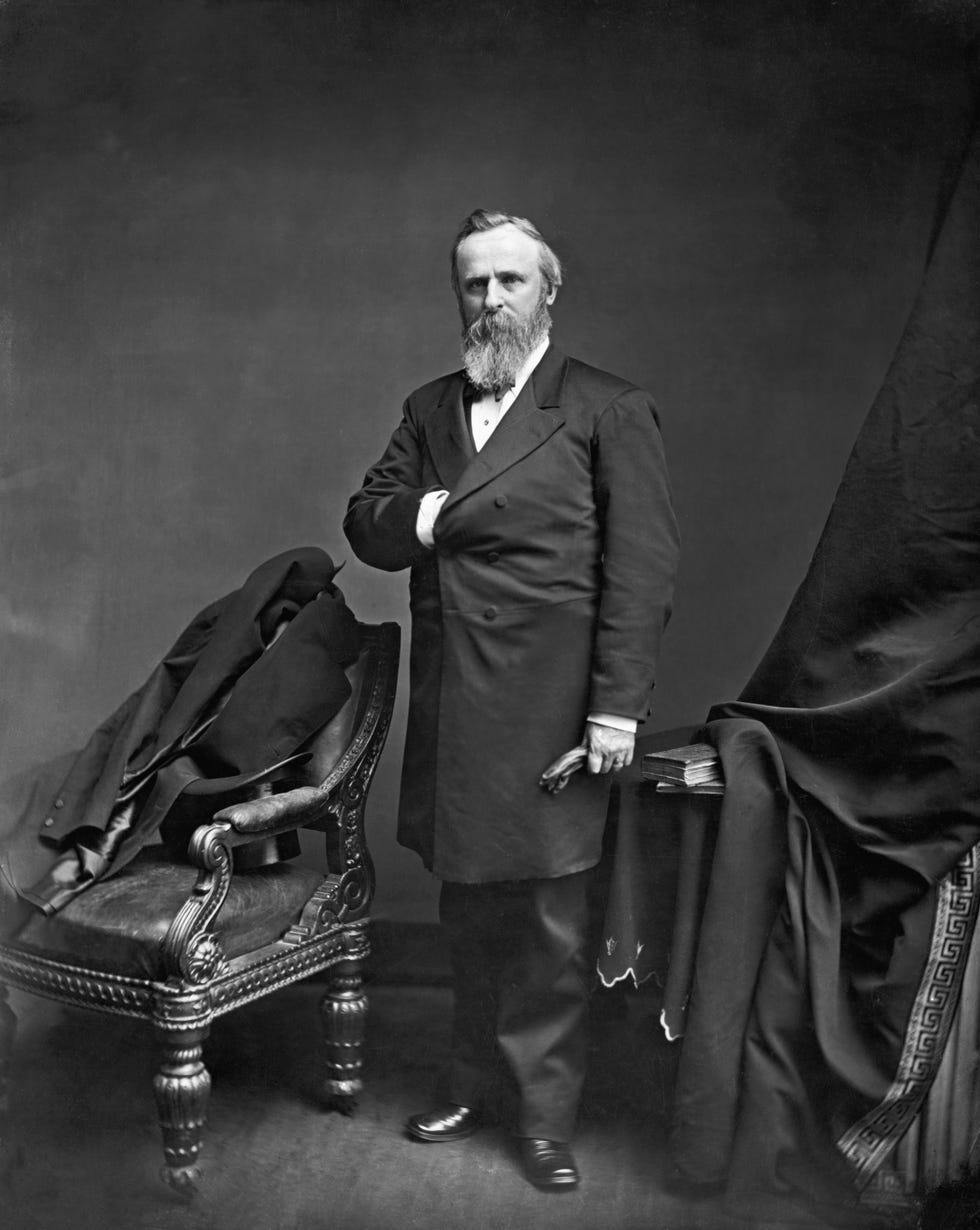

Rutherford ‘Rutherfraud’ Hayes entered the White House under a cloud of controversy

Ohio-born Rutherford B. Hayes was an attorney, Civil War veteran, Congressman and former governor of Ohio when he became the Republican presidential nominee in 1876. It was a time of great unease in American politics. Republican-led effort to secure the rights of African Americans in the former Confederacy, known as Reconstruction, was more than a decade old, and much of the country, both North and South, was growing weary of federal occupation of several Southern states. Republican President Ulysses S. Grant remained popular, but his administration was mired in scandal and an economic recession had taken hold.

On election day New York Democrat Samuel Tilden won a plurality of the popular vote. But when the votes in three Southern states seemed too close to call, a Congressional committee was convened and just days before inauguration day, Hayes was declared the winner. His opponents immediately cried foul, accusing Hayes and the Republicans of making a back-room deal (known as the Compromise of 1877) that gave Hayes the White House in exchange for his pledge to end Reconstruction — and dubbing him “His Fraudulency” and “Rutherfraud” Hayes. In truth, Republican leadership had all but decided to abandon Reconstruction before the election, with Hayes removing the few remaining federal troops months later. Despite the controversies surrounding his election, Hayes proved a competent, though cautious president, and easily won re-election in 1880.

William ‘Big Bill’ Taft struggled with his weight for most of his life

The only U.S. president to also serve on the Supreme Court, William Howard Taft was nicknamed “Big Lub” while a student at Yale and by the time he became Theodore Roosevelt’s secretary of war in 1904, he weighed more than 300 pounds. In an effort to shed the weight, Taft consulted a British dietician who put him on a restricted (for Taft, anyway) diet of high proteins and low carbs and insisted he keep a food diary. By April 1906, Taft had lost nearly 60 pounds.

But he eventually abandoned the diet, and by the time he was elected in 1908, he tipped the scales at more than 350 pounds. “Big Bill,” as he was also called, consumed an enormous amount of food each day, as detailed in a book by housekeeper, and bristled at attempts to restrict his diet. The oft-told story of Taft getting stuck in a White House bathtub isn’t true, but he did have specially designed and sized tubs installed for his use. Taft once again lost weight after leaving the White House, but the damage had been done and he died of heart disease in 1930.

Herbert ‘Great Humanitarian’ Hoover saved the lives of millions

While Herbert Hoover is remembered by many for his perceived lack of government intervention in the first years of the Great Depression, he won the White House in 1928 in large part thanks to his successful handling of a series of crises more than a decade earlier. When WWI began in 1914, Hoover was a millionaire engineer, but his Quaker upbringing led him to answer the call when famine threatened to kill millions of citizens in Europe. Hoover established a volunteer relief effort to send food to Belgium and France.

In 1917 he joined the newly-formed U.S. Food Administration, leading rationing and food conservation efforts upon America’s entry in the war. He continued his efforts after the war, and his American Relief Administration delivered more than 34 million tons of food to war-torn Europe and leaped into action in 1921, setting up camps in Soviet Russia that were soon feeding more than 11 million every day. Grateful citizens built tributes to Hoover, including a Belgian statue depicting him as the Isis, the Egyptian god of life.

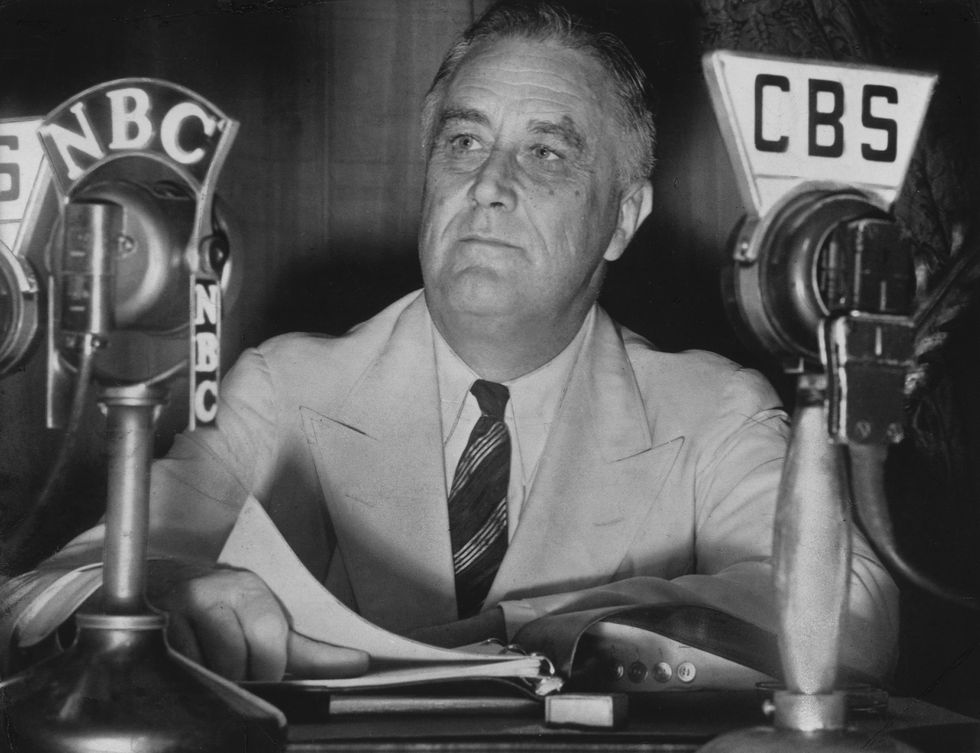

Franklin ‘Great Sphinx’ Roosevelt had a penchant for secrecy

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s patrician background made him an unlikely champion of the poor and downtrodden, and his election in 1932 and ushering of radical New Deal policies to end the Great Depression led many wealthy opponents to refer to him as a “traitor to his class.” For many Americans, Roosevelt was a national cheerleader, bucking up the country’s spirits with fireside chats and claims that America had nothing to fear but fear itself. But behind the public persona lay a more complex personality, prone to keeping secrets and holding his innermost thoughts to himself.

In 1939, as Roosevelt was deciding to run for an unprecedented third presidential term this inscrutability was on full display, leading reporters and political cartoonists to dub him the “Great Sphinx,” for his refusal to answer their questions. At an annual reporters’ dinner that year, Roosevelt was presented with an 8-foot tall papier- mâché sphinx in his likeness. Roosevelt, of course, ran and won, and the sphinx remains on display at his presidential museum.

Lyndon ‘Landslide Lyndon’ Johnson underhanded political dealings

Lyndon B. Johnson was born in a three-room house in rural Texas and his family often struggled to get by. He worked as a teacher in a predominately lower-class, Mexican American community before entering politics. In 1937 he won the election for a recently-vacated House seat and the 28-year-old Johnson began a decades-long Congressional career. In 1941 he lost a close race for the U.S. Senate, amid allegations of fraud on both sides.

Seven years later, Johnson made a second Senate run, only to be embroiled in another voting scandal during a Democratic primary runoff against popular Texas Governor Coke Stevenson. Early results on election day showed Stevenson with a clear lead, but the race suspiciously narrowed over as more votes were “found” and counted in the following days. While voting irregularities and outright stealing weren’t uncommon in Texas and elsewhere, the actions of Johnson’s team raised eyebrows. But his razor-thin, 87-vote victory was upheld, and the new Senator Johnson returned to Washington with a new nickname he found hard to shake: “Landslide Lyndon.” Despite how he’d earned his seats, Johnson became one of the most powerful Senators in history, then vice president and finally president, where, in 1964, he truly did win a landslide victory, capturing more than 60 percent of the popular vote (still a record) and more than 90 percent of electoral votes.

Richard ‘Tricky Dick’ Nixon wasn’t coined during Watergate

Two years after LBJ won his Senate seat, Richard Nixon was running a brutal campaign of his own in California. Nixon had been elected to the House of Representatives four years earlier, quickly gaining a reputation as an ardent anti-communist and famously playing a key role in the case against Alger Hiss, a State Department official alleged to be a Soviet spy. Nixon’s opponent was fellow Congressmember Helen Gahagan Douglas, a former actress who had become California’s first female Democratic representative.

The left-leaning Douglas was accused of having communist ties (no small fear at the height of the Red Scare), and her Democratic primary opponent had dubbed her the “Pink Lady.” Nixon capitalized on the accusations, but also made sure he covered his political bases. He sent out pink-hued pamphlets attacking Douglas’ loyalty. He used a loophole in California law to register on both the Democratic and Republican ballots, and then sent out mailers to hundreds of thousands of potential voters, some that falsely claimed that Nixon was a Democrat and others that tried to obscure his party affiliation altogether, in an attempt to attract voters who considered Douglas too radical. The Los Angeles Daily News (whose publisher was Douglas’ primary opponent) cried foul, running a series of pieces decrying “Tricky Dick” underhanded campaign, to no avail. Nixon easily won the election by more than 700,000 votes.

Ronald ‘Great Communicator’ Reagan helped transform presidential politics

As a child, Ronald Reagan had been nicknamed “Dutch” by his father, who thought his son “looked like a fat, little Dutchman.” The nickname stuck and was frequently used by family and friends throughout his life. His appearance in the popular 1940 film Knute Rockne: All American as Notre Dame football player George Gipp earned him another nickname for his deathbed plea that his team “win one for the Gipper.”

As Reagan made the transition from actor to public speaker to politician, he used the skills he’d developed to craft a unique persona and way of addressing his audience (and later voters) to twice win election as governor of California. In the late 1970s, The New York Times noted that Reagan was a “great communicator,” and the apt phrase stuck, as Reagan mastered mass media as a new political tool.

Thank you for reading this post 12 Presidential Nicknames and Their Unusual Origins at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search: