You are viewing the article 10 of Langston Hughes’ Most Popular Poems at Tnhelearning.edu.vn you can quickly access the necessary information in the table of contents of the article below.

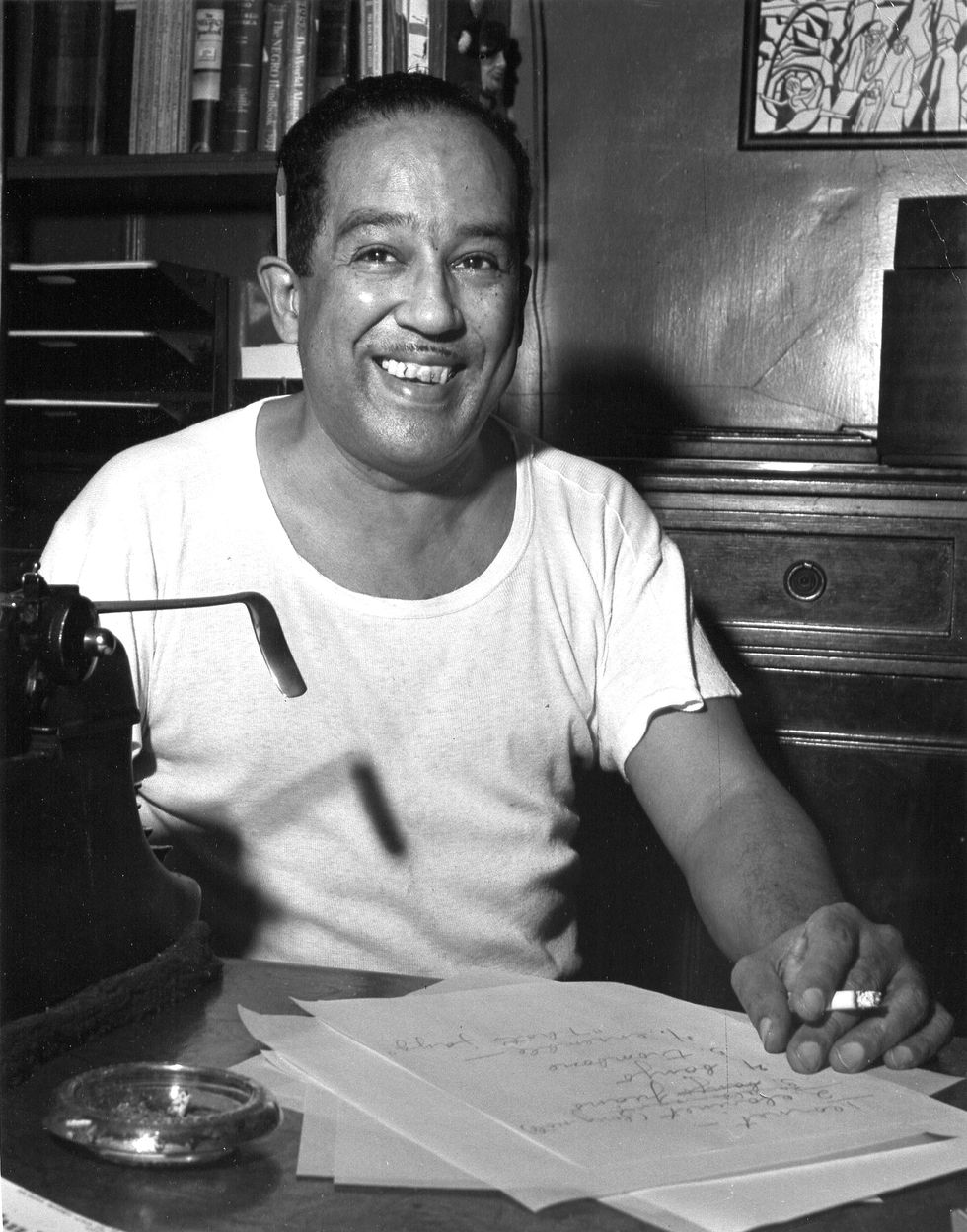

Langston Hughes, an American poet and social activist, is widely celebrated for his profound impact on the literary world. His unique style of writing, infused with powerful imagery and themes of race, identity, and the African American experience, continues to resonate with readers today. Among his vast body of work, there are ten poems that stand out as some of his most popular and influential compositions. From the timeless “Mother to Son” to the politically charged “Harlem,” Hughes’ poems offer profound reflections on the human condition and the struggles faced by marginalized communities. In this essay, we will explore ten of Langston Hughes’ most popular poems and delve into the themes and emotions that make them resonate with readers across generations.

In a 1926 story for The Nation, Langston Hughes wrote, “An artist must be free to choose what he does, certainly, but he must also never be afraid to do what he might choose.” And throughout his career, he crafted his words with that exact essence.

Born James Mercer Langston Hughes in Joplin, Missouri, on February 1, 1902, the young boy moved around throughout his early years growing up with his maternal grandmother after his parents’ divorce. When she passed away, he went to live with his mom in Cleveland, where he began to write poetry. After spending a year in Mexico with his dad, he enrolled at Columbia University in New York City in 1921 and became a leading voice of the Harlem Renaissance movement.

READ MORE: Langston Hughes’ Impact on the Harlem Renaissance

Though he dropped out of college and spent time in Africa, Spain, Paris, Washington, D.C., and Pennsylvania, much of his work focused on Harlem — where he eventually settled in 1947 in a three-floor brownstone on East 127th Street, which is now a historic landmark.

While Hughes is best known for his poetry — often marked with lyrical patterns — he also wrote novels like 1929’s Not Without Laughter, short stories like his 1934 collection The Ways of White Folks, his 1940s autobiography The Big Sea and lyrics for the Broadway musical Street Scene. He even worked as a war correspondent during the Spanish Civil War in 1937 for several American papers and as a columnist for the Chicago Defender.

Hughes died of complications from prostate cancer on May 22, 1967, but his influence continues both through his poetry and his theme of writing on dreams, which Martin Luther King Jr. is said to have derived his ideas.

Here are 10 of his most memorable poems:

“The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (1921)

Written when he was 17 years old on a train to Mexico City to see his father, “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” was Hughes’ first poem which received critical acclaim after it was published in the June 1921 issue of the NAACP magazine The Crisis. The opening lines show a soul deeper than his age: “I’ve known rivers / I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the flow of human blood in human veins / My soul has grown deep like the rivers.” The style honors that of his poetic influences Walt Whitman and Carl Sandburg, as well as the voice of African American spirituals.

“Mother to Son” (1922)

With recitations from notables ranging from King to Viola Davis, “Mother to Son” was first published in the December 1922 issue of the magazine The Crisis. The 20-line poem traces a mother’s words to her child about their difficult life journey using the analogy of stairs with “tacks” and “splinters” in it. But ultimately she encourages her son to forge ahead, as she leads by example: “So boy, don’t you turn back / Don’t you set down on the steps / ’Cause you finds it’s kinder hard / Don’t you fall now / For I’se still goin’, honey / I’se still climbin’ / And life for me ain’t been no crystal stair.”

“Dreams” (1922)

One of several Hughes poems about dreams, appropriately titled “Dreams,” was first published in 1922 in World Tomorrow.” The eight-line poem remains a popular inspirational quote: “Hold fast to dreams / For if dreams die / Life is a broken-winged bird / That cannot fly. / Hold fast to dreams / For when dreams go / Life is a barren field / Frozen with snow.”

“The Weary Blues” (1925)

“The Weary Blues” follows an African American pianist playing in Harlem on Lenox Avenue. While it starts off sounding like he’s completely carefree, it ends: “The stars went out and so did the moon / The singer stopped playing and went to bed / While the Weary Blues echoed through his head / He slept like a rock or a man that’s dead.” After it won a contest in Opportunity magazine, Hughes called it his “lucky poem.” Sure enough, the next year, his first poetry collectionwas published by Knopf with the same title when he was 24.

“Po’ Boy Blues” (1926)

As one of four Hughes poems that appeared in the November 1926 issue of Poetry Magazine, as well as his collection The Weary Blues, the poem feels music-like with its stanza and rhymes. The final verse reads: “Weary, weary / Weary early in de morn. / Weary, weary / Early, early in de morn. / I’s so wear / I wish I’d never been born.”

“Let America Be America Again” (1936)

First published in the July 1936 issue of Esquire magazine, “Let America Be America Again” highlights how class plays such a crucial role in the ability to realize the promises of the American dream. The three opening stanzas are each followed by a parenthetical representing the cast-off realities for the lower class, such as: “Let America be America again / Let it be the dream it used to be / Let it be the pioneer on the plain / Seeking a home where he himself is free / (America never was America to me.)”

“Life is Fine” (1949)

Perseverance pushes through all the odds — even suicide attempts — in “Life is Fine.” Broken into three sections, the first part talks about jumping into a cold river: “If that water hadn’t a-been so cold / I might’ve sunk and died.” And the second about going to the top of a 16-floor building: “If it hadn’t a-been so high/ I might’ve jumped and died.” But in the third section, it says, “But for livin’ I was born” before ending with “Life is fine! / Fine as wine! / Life is fine!”

“I, Too, Sing America” (1945)

Also known as just “I, Too,” Hughes addresses segregation head-on: “I am the darker brother / They send me to eat in the kitchen / When company comes.” Despite being hidden in the back, he continues to “laugh,” “eat well” and “grow strong.” But he looks to a future of equality: “Tomorrow / I’ll be at the table / When company comes. / Nobody’ll dare / Say to me, / “Eat in the kitchen” and ends with “I, too, am America.”

“Harlem” (1951)

Perhaps his most notable work, “Harlem” — which starts with the line “What happens to a dream deferred?” — was actually conceived as part of a book-length poem, Montage of Dream Deferred. The words dig into the dichotomy of the idea of the American dream juxtaposed with the reality of being in a marginalized community. With more than 90 poems strung together in a musical beat, the full volume paints a full picture of life in Harlem during the Jim Crow era, most questioned in the poem’s final line “Harlem” with “Or does it explode?”

“Brotherly Love” (1956)

Despite the fact that Hughes was more of a household name than King at the time, the poet wrote “Brotherly Love” about the civil rights activist and the bus boycott, which starts: “In line of what my folks say in Montgomery / In line of what they’re teaching about love / When I reach out my hand, will you take it — / Or cut it off and leave a nub above?” It continues, “I’m still swimming! Now you’re mad / Because I won’t ride in the back end of your bus.”

In conclusion, Langston Hughes’ most popular poems are timeless works of art that continue to resonate with readers from all walks of life. Through his powerful use of imagery, rhythm, and language, Hughes tackles important themes such as racial inequality, the African American experience, and the search for identity. Whether it’s the harrowing plea for equality in “Let America Be America Again” or the soulful celebration of black culture in “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” each poem showcases Hughes’ unparalleled ability to capture the essence of human emotions and experiences. These poems serve as both a reflection and critique of society, urging us to confront our societal injustices while also celebrating the resilience, beauty, and power of the human spirit. Langston Hughes’ legacy as a prominent figure in the Harlem Renaissance and a pioneering voice in African American literature continues to inspire and captivate readers, reminding us of the enduring power and importance of his words.

Thank you for reading this post 10 of Langston Hughes’ Most Popular Poems at Tnhelearning.edu.vn You can comment, see more related articles below and hope to help you with interesting information.

Related Search:

1. “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” by Langston Hughes

2. “Dreams” by Langston Hughes

3. “Harlem” by Langston Hughes

4. “Mother to Son” by Langston Hughes

5. “I, Too” by Langston Hughes

6. “A Dream Deferred” by Langston Hughes

7. “Still Here” by Langston Hughes

8. “Let America Be America Again” by Langston Hughes

9. “The Weary Blues” by Langston Hughes

10. “Life is Fine” by Langston Hughes